On Political and Societal Divisions

Is it a flaw within our nation’s political system that in order to gain enough support from one’s political party, a politician must take positions that antagonize a sizable portion of the population on the other side of the political spectrum? A study (Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape) of 8,000 people in the United States found that 8% of people belong to the most liberal group, considered “progressive activists,” 6% belong to the “devoted conservatives” group, and 19% to the “traditional conservatives” group. The rest, 67% of the people surveyed, belong to the “exhausted majority” group. This group shares “a sense of fatigue with our polarized national conversation, a willingness to be flexible in their viewpoints, and a lack of voice in the national conversation.”

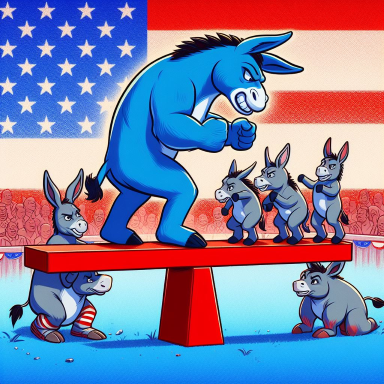

There is nothing inherently wrong with having strong beliefs. But it is important for people who do not have as strong beliefs on issues to feel like they do not have to choose between one extreme side or the other. I believe the problem is that the vast majority of Americans who lean one way or the other, but are open to reasonable dialogue, are forced to pick a side. This is because the extremes are gaining louder and louder voices within each side and the middle is quickly disappearing.

A consequence of this, is people feel more personally attacked by the other side. Feeling attacked naturally causes a reaction against the source of the attack. This often leads people who have moderate views and are willing to hear out people with different opinions and experiences, to adopt more extreme version of their views as a defense mechanism. This process is self reinforcing. One person becomes more extreme in response to what another said, and then the other person becomes more extreme in response to that.

Where does this come from? It comes from a political system that incentivizes political parties to highlight and exploit disagreements between people in different “groups.” It comes from a system that incentivizes a political party to make an opposing party’s administration unsuccessful, so it can win the next election. But most of all, it comes from two sides that have different conversations about the same issues, straw-manning each other. Every issue that the two parties disagree on is nuanced. But neither side wants to talk about the nuance, because in doing so, they would be admitting that the other party does have a point in what they are advocating.

Why do the interests of white working class citizens and immigrants and minorities necessarily have to be opposed? Why can’t we admit that the vast majority of America abhors racism and believes in fair treatment to all, but not dismiss the subtle racism in everyday life and the legacy of the structures and attitudes of racism in this country? Can we not admit that, even with its flaws, the US has one of the best track record on fair treatment and rights for all? Shouldn’t we understand that wanting legal immigration is not racist? But also understand the plight of individual immigrants is difficult and thus be compassionate about it?

Can’t we understand that objecting to having more of your money taken away when you make more, and wanting tax cuts does not make you uncaring of the poor? At the same time, can we understand how hard it is for many working people to make ends meet? And not suggest that giving them more of a helping hand is just a handout that encourages laziness? Obviously, bridging the gap requires more nuanced takes than these rhetorical questions. But they should indicate that both sides of most arguments have kernels of truth in them. This isn’t to say that both sides are equally valid. But a better way of discourse is recognizing that there are legitimate claims for the other side, and responding to them. Not demonizing another argument as beyond the pale right off the bat.

You don’t have to cater be a little bit of both sides of every issue mentioned. You don’t even need to be in the political center. One side is not necessarily as right as the other. But if you caricature one side as all the worst things you can imagine about them, don’t expect anything positive to come out of it. In fact, you should expect the other side to do the same of you. You have to believe that almost all people want what is best for the country, and what is most fair and just. It’s perfectly fine to have disagreements and fight for what you believe in, but understand that people’s views are nuanced and complex, just like their lives.

One of the simplest ways to do this is have more face to face conversation. When you do that, you are able to communicate more clearly. You are able to attach a face to the argument; they become a real person. You also get the feeling that you actually know the person. Another is to limit the amount of time you spend in your ideological bubble. When you are constantly hearing about how bad the other side is with no counter, you create a distorted view of them. Try to understand how they think and see the world. But also, limit the amount of time you focus on politics in general. People are people. Regardless of political beliefs, they are generally friendly with each other. When you form a human connection with someone you disagree with, you see that maybe their ideas aren’t so extreme after all.

Don’t buy into the idea that everyone falls neatly into a group that is either good or bad, oppressor or oppressed, privileged or not privileged. Even if there are shades of truth in distinguishing different groups of people, the best way is to sit down and have an honest conversation with those you disagree with.